An introduction to

Uranium Companies

15/05/2020

The time has come to start digging into uranium companies. This is a long write-up so I would advise those of you who are a bit more impatient or that just don’t have the time to read it all in one go, to read it in tranches as if it were several different analyses.

The first part of this write-up is where I outline the strategy to find and invest in uranium companies, the second one is a look at Cameco and the third one is a look at Denison Mines. I must also warn you that these aren’t super hot companies. We’re not talking about Amazon or Facebook here. Although what I want from this first phase is to get a birds-eye view on these companies, I won’t be able to avoid some technical stuff. After all, this is mining.

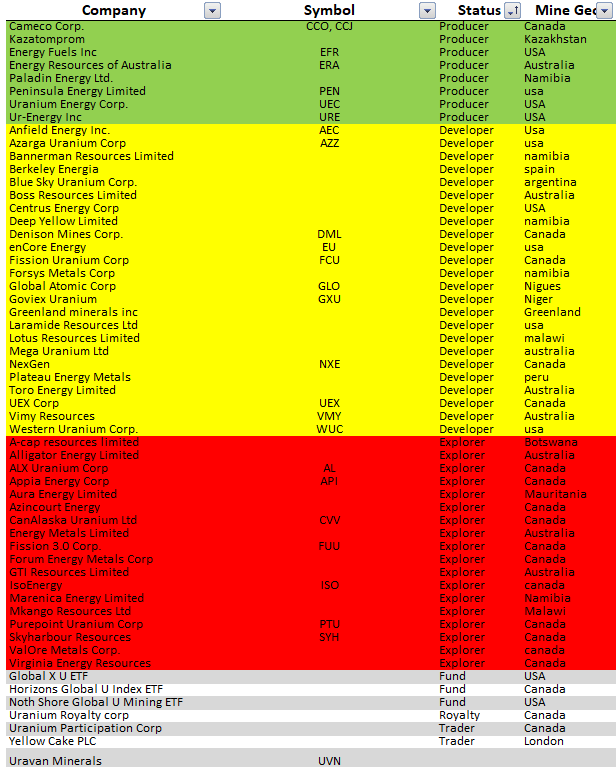

There are about 50 publicly traded uranium miners out there. 8 are producers, 23 are developers and the rest are explorers. Add to those a few financial players and a couple of funds. Which one offers the better risk-reward? That’s what I’ll be looking to answer in the coming weeks.

Roughly speaking, a producer is a company who is already in operations. A developer is a company that has already found an ore body in the ground and is preparing to mine it and an explorer is a company who is still looking for ore. Generally speaking, the risk of investing in these companies is inversely proportional to their stage of development. The explorer is riskier than the developer and the developer is riskier than the producer. This makes sense, right? To whom would you lend your money first? A guy who is still drilling holes in the ground trying his luck or a guy who has already dug the hole and is selling the product?

I’m not going to be looking at all of the uranium companies for several reasons. The first one is that, although there are far fewer uranium companies today than there were in the last bull market, they are still too many. Then, it’s not as easy as looking at a meatball company. You see, when fund managers want to invest in explorers (or even developers), they hire mining engineers specialized in uranium mining to help them evaluate the company’s resources, costs, etc, in order to understand which CEO is lying the less. Someone once said that “a mine is a hole in the ground with a liar on top“. When I first started learning about uranium, I was perplexed at the fact that several investors publicly stated that a miners job was to lie better than its competitor. What did this mean?

Mining is probably the worst industry on the planet. Depending on the specific sector (uranium, precious metals, rare earths, etc) there are nuances, but uranium being a cyclical commodity, there will be long periods of low prices and if a company hasn’t been able to sign enough long-term contracts when the times were good or if it isn’t in production yet, it will have to raise cash, usually by issuing new shares (there aren’t a lot of banks lending money to these lousy businesses with no cash flows), thus diluting the existing shareholders at the worst possible time, which is when the share prices are at their historical lows. This means that to get $1 dollar, the company will have to issue a lot more shares than if the shares were more expensive. Not a good situation for existing investors. And it’s this need for cash, often in the worst possible time, that turns most of these CEO’s into highly skilled salesmen making the job of the investor a lot harder.

And that’s also the reason why most of the expert speculators in this field prefer to “play” these companies, not by buying their shares, but by lending them money with the possibility of converting that debt into shares at reasonable valuations when the cycle turns. This is called convertible debt (there can also be warrants and other financial instruments, but let’s not get into that right now). One of the good thing about lending money is that you don’t get diluted. Because this is such a lousy business, interest rates are high so the lender gets a good return on his money and if anything goes wrong with the company, he has the right to receive his money ahead of the shareholders. If you add to this the possibility to convert this debt in equity at $1 when the share price is $3, so much the better.

Have you noticed that I said speculators instead of investors back there? That’s right. There is a subset of investors who are highly specialized in mining and these guys aren’t usually called investors, but speculators. They are speculating that the price of a commodity is going higher. One of the most famous ones – if not THE most famous one – is Rick Rule. You can watch one of his latest interviews HERE.

Checklist

But I digress. With so many companies at such different stages and with so many technical terms (wait for it) and so many peculiarities, it’s easy to become overwhelmed if we don’t follow a method. This is what I did: I’ve read and heard all the experts, investors and most of the CEO’s, took notes on what they focused on the most and then I cross checked all of those inputs to compile a detailed checklist that will allow me to stay the course while standing on the shoulder of giants:

- Proven management (and directors): There is no way I can stress this enough (even to myself). MANAGEMENT, MANAGEMENT, MANAGEMENT. This is THE industry where you need to stand behind the guys who have done it before. From raising money to actually mining the ore, to shiping it, to having negotiated with clients before… Damn, there are CEO’s out there who don’t even know how to get to their clients simply because they have never done it before. This is probably the most important thing on this list. Add to it the fact that the last great uranium cycle was back in 2003/2011. From then on, “nothing happened”. This means that there aren’t that many experts out there. That’s why you need to focus on companies that are run by people who have done it before. Insider ownership and shareholder friendliness are definitely a plus.

- Strong balance-sheet: I honestly don’t know what kind of balance sheets I will run into, but if this cycle takes a little longer to turn and if a company has a weak balance sheet, it will suffer (or even cease to exist).

- Shorter time to production: this is even more important than having a low cost operation given that in a shortage scenario the price you pay might not be as important as the availability of material. I should also add the lower capital expenditures needed to ramp up production in here as well. There are several mines that are in Care & Maintenance that can come online much faster than companies that still need permits. Pounds in the ground will be rewarded later in the cycle. Since there are several companies who aren’t producing yet, they just have pounds of uranium in the ground. CEO’s will try to sell their story by alluring potential investors with the Amazing SUPER – HIGH – GRADE reserves they have. Although pounds in the ground is a good thing, you’ve got to be carefull with the Siren’s song. It will be in a later stage, when uranium is scarce and utilities panic that these companies will benefit. Some of them will never be mined.

- Low cost: The cheaper the product, the earlier these companies are going to sell it and the earlier they get the much-needed financing to mine it.

- Good jurisdiction and permitting: mining takes a lot of permitting, a lot of infrastructure so a friendly set of laws is crucial. If the company you’re studying is trying to develop a mine in a country with no history of mining, forget it. You want mines that have good roads next to them with good access to a nearby port and all the permitting in place (or close to it). There are many different types of permits, from excavation permits, to exporting permits, to permits to handle radioactive material, you name it. Some uranium friendly countries are Kazakhstan, Canada, Australia, Namibia, among others.

- No exploration companies: At least, not just yet.

- Quality of ore: this is an obvious one, but I’ll add it here as well. The higher the grade of uranium in the rock, the lower the cost to mine each pound.

- Alternative sources of revenue or hidden assets: Mines that don’t depend solely on uranium are a good thing to look for. If a mine can profitably mine copper as well as uranium, there will be cash flows coming in from both commodities, de-risking the “play”. Similarly, if a company has a fully permitted mill, it will have another great source of revenue.

- Financials: In a first stage, look at the cash the company has in the bank, then the cash burn in the past 12 months and understand if the company will need to raise capital. How much? Is it being properly employed? On a second phase, understand the level of profitability at full capacity.

- Capital Structure: How cash flows to the various security holders within the capital structure (debt holders, preferred stockholders, convertible debt holders, common stockholders, etc). Understand the dilution and what the company did with the money.

- Valuation: It all comes down to this, right? There are several ways to go about it. One is to estimate the cash flows, apply a multiple and calculate the annualized return (if it’s a producer). Another one is to divide the Enterprise Value (market capitalization + debt – cash) by the pounds in the ground and compare it to peers.

This checklist should help narrow down the universe of uranium companies to be studied. By staying away from the explorers, we’re still left with 8 producers, 23 developers and 2 financial players. Still a lot of companies to look at. I am confident that after looking at the first three or four, I will be able to quickly dismiss some of the others. It’s like the negative art Ben Graham mentioned on his book Security Analysis. You’ll want to be looking for the bad companies and by excluding them, hopefully, you will be left with the good ones.

Strategy

When investing in uranium miners, the most sensible approach is to buy a basket of companies, not a single one. Why? For starters, mining is such a lousy activity that if you “bet” on one company and its largest mine gets flooded (as it happened to Cameco in 2003), you will have blown it. There are a lot of unforeseen dangers like this in every mining operation so diversification is important. Another reason is to insulate yourself from bad management. It’s not that if you bet on 5 different bad managers you will get the equivalent to 1 good manager, but if one behaves badly, you won’t lose much.

As a general rule of thumb, I will want to get in the first-to-market players right now and then I might shift into some of the riskier names.

Exit Strategy: If there is a type of investment where you definitely need to have an exit strategy, cyclicals is the one. Depending on the commodity, there are several ways to go about it. One of them is to look at the multiples at which the stocks are trading for. After a great run-up, the multiples will compress, indicating that investors are preparing for a downturn. The problem with such strategy is that we become followers, and in an industry that “goes up through the stairs and comes down through the elevator” it’s much better to be early and leave some money on the table than to be late and loose a good chunk of the profits. Having said that, a good indicator is the Spot price itself. As a first rule I will start backing out when/if the spot price gets too lofty. What is a lofty price? I would say that around $70 is when I’ll start thinking about taking some money off the table. Will it ever get there? I have no clue, but if history is any guide, we might see even higher prices.

Another tell sign that we’re reaching the top will be when we see Rick Rule on CNBC talking about uranium. That will be a good time to start taking some money off the table. I’m not the one saying it, Rick is. But then again, he also acknowledges that he is frequently early in both buying and selling.

Now that the road-map is set, it’s time to start looking at some companies. Where should I start? Well, I could start with the A’s, but I believe there is a better strategy. What I have done was to compile a list of the best uranium investors out there and track their holdings. Whenever I see the same company on several different portfolios, I know I should be looking at it.

This week I’ve decided to look at 2 different companies that I hear about quite often: A producer (Cameco) and a developer (Denison Mines). By first looking at these two, I hope to get a feeling for each different stage of production and to be able to understand the following ones much faster. I won’t be looking at every single metric on this first stage. What I aim for is a birds-eye view of each one so I can then zero in on those which I suspect will be the best investments.

Cameco

Symbol: CCO (Toronto Stock Exchange) and CCJ (New York Stock Exchange)

Share Price: CAD$13,94

Market Cap: CAD$5,52B

Cameco is the bluest of the blue-chips of the uranium world. Whenever Cameco speaks, everyone listens. It’s run in a fairly conservative way by a top-notch management team headed by Tim Gitzel (CEO) and Grant Isaac (CFO) and it owns some of the best mines in the world situated in the famous Athabasca Basin (Basin). The Athabasca Basin is the most famous uranium mining region in the world. It’s situated in Canada in the middle of nowhere. You’ve got to be Frodo to be able to get there without an airplane. That’s why every single mine has its own landing strip (Google it). Miners will fly-in fly-out just to get to work.

I don’t intend to be very descriptive here, but I feel that a quick overview of Cameco’s most important assets is important:

McArthur River: Located in the Basin, it’s currently on Care & Maintenance since 2018. Owned 69,8% by Cameco, it’s an underground mine with an average grade of 6,91%, proven and probable reserves of 274 million pounds and an annual output of 18 million pounds. Estimated cash-cost per pound is CAD$14,97.

Cigar Lake: Also underground and located in the Basin, it has been put on Care & Maintenance in March 2020. It’s owned 50% by Cameco with proven and probable reserves of 86,3M/lbs (Cameco’s slice) at an average grade of 15%. Its 2019 production was 9 million pounds (Cameco´s slice) which means that the mine will be depleted this decade (and Cameco will have to substitute it with another mine which will probably be acquired). Estimated cash-cost per pound is CAD$15-$16.

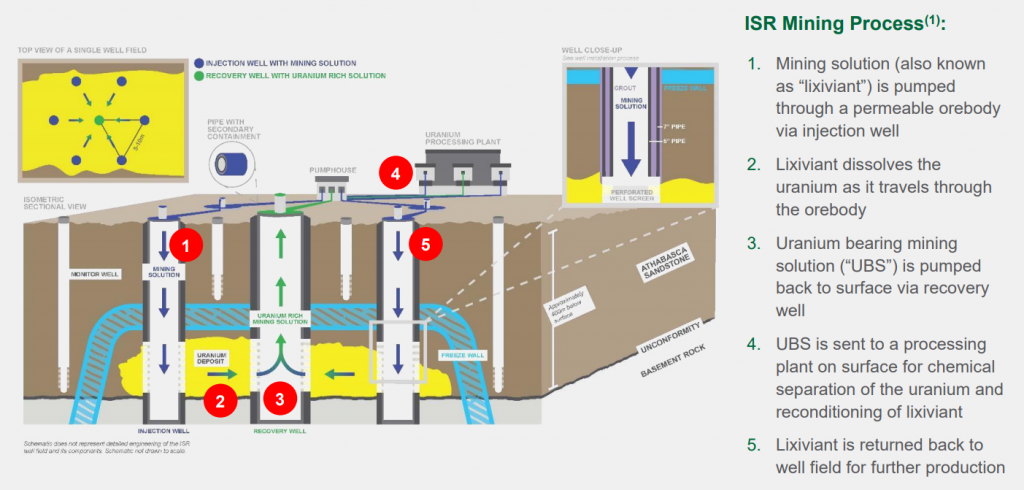

Inkai: An In Situ Recovery mine located in Kazakhstan. This is a joint-venture with Kazatomprom (the biggest uranium miner in the world). Cameco owns 40% of it. At an average grade of 0,03%, its estimated reserves are 100M/lbs (Cemeco’s slice) and its 2019 production was 3,3M lbs (Cameco’s slice) in 2019. Estimated cash-cost per pound is CAD$8-$9.

Then there is also the world’s largest commercial uranium refinery in Blind River, the Port Hope Conversion Facility where Cameco controls 25% of the world’s conversion capacity and some more assets. Unlike the majority of he mining companies, Cameco is vertically integrated, meaning that it controls the production from beginning to end.

Until recently, their only two operating mines were Cigar Lake and Inkai, but as I’ve mentioned above, they’ve suspended the Cigar Lake mine back in March so the only mining operation they are running is Inkai and even that one will see its output reduced by 12% this year.

Cameco’s average annual sales commitments are 19M/lbs for 2020 up to 2024, but this isn’t evenly distributed. In their 2019 Annual Report they’ve said that they would be buying between 20 to 22 million pounds in 2020 to fulfill their commitments of 28-30 million pounds. The balance would be met by Cigar Lake and Inkai. But now they don’t have Cigar Lake. Assuming that their commitments will stay the same, they will have to buy between 25 to 27 Million pounds in the Spot Market. That will be interesting to watch given that last year they had trouble buying 19 Million pounds. Now there is less inventory out there and they are willing to buy more of it. That will have a double-benefit. It will not only take uranium out of the spot market but it will also drive the price higher.

STRATEGY

Cameco is the most well known uranium company for some reason. These guys have a well-thought out strategy and they’re sticking to it. They’ve made it their mission to take all the inventory they could out of the spot market. They have been waiting for this moment for years. I don’t mean to be mean here, but this whole virus thing has come in handy for these guys. What they’ve been saying to the market as of lately is: We will shut down our mines and we’ll buy from the spot market until there is no inventory left out there and utilities will have to come to us and sign contracts. Then, we will be able to call the shots. They didn’t actually say that. I did. But it’s what they meant.

What they’ve repeatedly said is that they need the price of uranium to go above US$40 in order to start signing contracts and get back to production. Their production costs in 2019 were $32 per pound (including non-cash costs) and $15,7 per pound (cash-costs). At the current US/CAD conversion rate of 1.41, and if they were signing contracts at US$45, they would be generating about $48 in cash per pound (45×1,41-15.7=48). But now that they’re seeing the spot price recover, they’ve been hesitant to talk about $40 and I suspect that they will raise that number soon.

Either way, if they keep delivering 30M/lbs per year at a $48 profit, they would be making $1,5 billion per year. At today’s market cap of CAD$5,5B, this would mean a P/FCF of 3,8. Now, you can argue that I left several important costs out of my back-of-the-napkin valuation such as interest costs, depreciation, royalties and the likes. And that’s true. But I also left out the operating leverage these businesses have and the very likely possibility for these guys to sell much more than 30 Million pounds per year, so… Let’s agree to the following. If after looking at a few more companies I feel that Cameco might be interesting, I will do a proper valuation. In the meantime I would say that we can easily be seeing Cameco trading for a multiple of 10x which would mean a triple in share price from here. When will that be? I have no clue. But even if it’s in 10 years from now – which I doubt – that would mean an annualized rate of return of 11%.

Coming back to their strategy, these guys have prepared in advance, they’ve reduced costs, reduced the dividends, reduced inventory and strengthened the balance sheet so they can be in a bargaining position right now. They don’t need to sign the first contract that is presented to them. They will only sign on their terms. They can leave those mines offline for “as long as they want”. It seems that the table has turned and we’re now entering a sellers market rather than a buyers market.

When they finally get back into production, they will first fully contract Cigar Lake and only then will they resume operations at McArthur River. That’s why some specialists say that McArthur River won’t come online until 2022 or 2023. Unlike McArthur River, Cigar Lake can resume production in a short period of time. All the workers are in standby mode. McArthur River on the other hand will take 9 months just to restart and Cameco will get just 4M/lbs out of it in the first year (18M/lbs in subsequent years). You see, they had to fire everyone. They will have to hire and retrain all of those workers before restarting production.

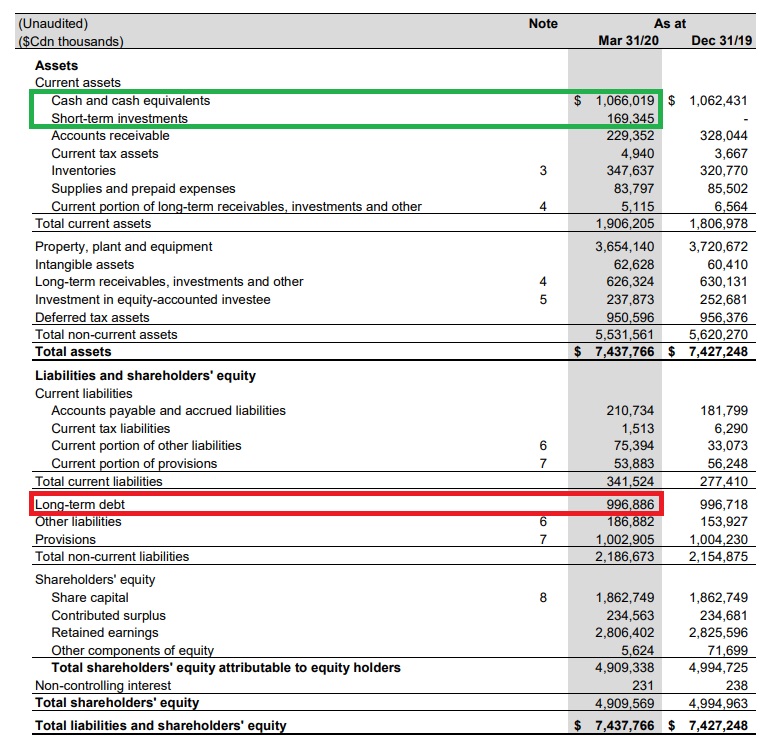

Balance Sheet: As I’ve said above, I do not intend to look at all the financial metrics of each and every company at this stage, but a quick glance at the balance sheet is of the essence. The company has CAD$1,2 billion in cash and an undrawn credit facility of CAD$1 billion which it doesn’t expect to be needing in the near future. It also has $1 billion in long-term debt (maturities in 2022, 2024 and 2042). Surprisingly, it’s has been cash flow positive for the past 5 years without issuing a single share so I’m not worried about liquidity issues right here.

“A restart decision is a commercial decision that will be based on our ability to commit the production from this operation under acceptable long-term contracts” Tim Gitzel, Cameco’s CEO

CAMECO CONCLUSION

Summing up, Cameco is a blue-chip that has great assets which can be mined at a low-cost and that can come online pretty quickly. It has a great management team who runs it in a conservative way, it has a solid balance sheet so i would say this might be a good low risk – medium reward investment compared to some of the other names. By the way, when I say medium reward, I’m talking about at least a double or a triple from here. Let’s now look at a completely different story.

Denison Mines

Symbol: DML (Toronto Stock Exchange), DNN (New York Stock Exchange)

Share Price: CAD$0,59

Market Cap: CAD$369M

Denison Mines is a Canadian exploration and development company whose prime asset is the Wheeler River Project, also situated in the Basin of which it owns 90%.

Denison Mines also has a 22,5% interest in the McClean Lake Mill (70% Orano and 7,5% OURD), which is currently processing ore from the Cigar Lake Mine (Cameco) under a toll milling agreement – which means that Cameco uses the facilities and pays for that usage. The mill is licensed for 24 million pounds and is currently processing 18 million pounds so it still has 6 million pounds of idled capacity.

My first thought was that with the Cigar Lake being suspended by Cameco, Denison Mines would suffer without the revenue stream coming from the mill, but then I found something out. Although the company owns 22,5% of the mill, it has sold the revenues that come from the toll agreement to Anglo Pacific Group back in 2017 for $43,5 million in order to fund its operations. Smart move. Instead of collecting the payments every year from Cameco, they effectively borrowed against that revenue stream so they don’t have to wait for the ore to be processed. Yes, the interest rate is high (10%) but it was a smart move nonetheless and it goes to show the type of creative financing these companies can come up with.

The company also owns several other assets, one of them being a 15% stake in Goviex Uranium (TSX-V: GXU) which I will probably look into in future analyses.

On top of that they also manage Uranium Participation Corp (TSX: U), which is an interesting company that owns uranium but doesn’t mine it nor does it sell it, and they still own an environmental services business located in Elliot Lake. They take care of mines that are in Care & Maintenance mode.

Coming back to the Wheeler River Project, the CEO says that it’s the “largest undeveloped high-grade uranium project in the Basin“. It has two mines: Phoenix and Gryphon which are 3 Km apart. Phoenix is super low-cost because it can be mined through the In Situ Recovery method. This will be the first mine to come online between the two. The Athabasca Basin is similar to a bathtub. You’ve got the porous sandstone in the middle and the hard rock surrounding it. The sandstone in which Phoenix’s deposit is located is water-saturated and must be artificially frozen. Although this freezing process is quite common in the basin, it has never been done for an In Situ operation, so it presents some risk.

Gryphon, on the other hand, is hosted in the basement rock which allows it to be mined as a conventional underground operation.

Phoenix has 70M/lbs of reserves at a 19,1% grade. It’s estimated cost of production is US$3,3/lb, which is the lowest in the world. Gryphon has somewhere in between 65-70M/lbs at a 2% grade and an estimated cost of production of US$11,7/lb. These are just the operating costs of each mine. It doesn’t account for initial Capital Expenditures (that will flow through the Income Statement as Depreciation) nor does it account for corporate expenses such as G&A, interest, etc. All of these combined would be called the All in Sustaining Costs (AISC). The AISC for Phoenix are expected to be US$8,9/lb whereas for Gryphon they’ll be US$11,7/lb. Either way, these are extremely low values and Phoenix should be massively profitable.

This also means that it almost doesn’t matter what the price of uranium is for these guys to get financing. I say almost because they have been funding operations by issuing shares and the more expensive the shares, the better for the company and for the existing shareholders, not so much for the new ones.

To initiate production in Phoenix, the company needs a meager $325 million. Yes, it’s almost the company’s current market cap, but in an industry where you frequently hear about ramp up costs in the order of the billions, this seems pretty reasonable to me.

The company’s Pre-Feasibility Study (PFS) – which is one of the many studies miners do – estimated that they could start pre-production activities in Phoenix by 2021 and production in 2024, but as all things mining, another roadblock has arisen. It seems that now with the COVID-19 situation these deadlines will be postponed. 2024 seems very far away, right? In the uranium world, 2024 is tomorrow. These companies are like Ents, the tree shepherds in Lord of The Rings. In order to get to Isengard, they must leave the forest several months in advance.

STRATEGY

The management is pursuing the right strategy. They are focusing on getting into production rather than increasing its “pounds in the ground” portfolio before its two neighbors (Nexgen and Fission) come online. You see, utilities won’t sign contracts with companies that are not producing (or close to it) in a first phase. If the stars align and they can get the permit at the right time, this could be a Home run. Going forward, the company needs to 1) finish its Environmental Assessment and initiate permitting, 2) complete a final Definitive Feasibility Study and other technical studies and 3) get the financing to start the operations.

MANAGEMENT AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS

The moment I saw the CEO’s face I was like You’ve got to be kidding me!. This guy is my age (I’m 36 and he’s 37 years old). It’s not possible that he went through the last cycle already working in uranium. Well technically, it is possible, but I doubt it that he held a relevant role back then.

Then I started digging. The chairman, Catherine Stefan has been involved in mining companies for a long time. She is also a director at the Lundin Mining Corp. For those of you who don’t know, the Lundin family is probably the most important mining family in the world. So, if this lady is both the Chair in Denison Mines and a director in the Lundin Mining Group, she must be good. Then I found another Lundin related director. Ron Hochstein is currently the CEO of Lundin Gold. And then there’s Jack Lundin, son of the billionaire Lukas Lundin himself, who was once the Chairman and even tried a merger with Fission Uranium. Ok, so the plot thickens. It’s obvious that the Lundin family exerts an unusual influence over the board of directors and according to the website for the Lundin Group, Denison Mines are a part of the Group. The problem is that I can’t find their share of the company.

As far as I can tell, the largest shareholders are the Korea Electric Power Corp(KEPCO) and some funds from which I recognise Old West Investment, Joe Boskovich’s fund. Joe has been investing in several uranium companies as of lately. I have sent him some questions this week regarding the Lundin’s but I still haven’t received a reply. I will update you when I get those answers.

Regarding the director’s compensation, I found it to be very modest.

Regarding the management’s compensation, they are compensated with a cash-salary, annual performance incentives and equity bonuses. The salary is acceptable. The performance incentives can go up to a maximum of 80% of the cash-salary for the CEO and 50% to the CFO.

A part of these performance incentives is tied to several performance indicators such as the share price appreciation (by itself and in comparison to a peer group) which I tend to turn up my nose at because it might make them more promotional than they should. This is debatable, but should a CEO be paid based on what the market feels about his company? What about when the market gets nutty (as it does in uranium) and makes the share price go through the roof without the CEO having done a thing? Should he be paid for that?

But even more ridiculous is that in 2018, while the share price was down by -6.7%, several managers have received bonuses for outperforming the peer group which had seen its combined share price go down by -25.21%.

The compensation scheme for these guys is long and I should be reviewing it deeper if, after looking at several other companies, I find that Denison might be a good investment opportunity. For now, I’ll just leave the management’s compensation table below so we can compare it to the rest of the developers.

FINANCIALS

As I’ve briefly mentioned above, although the company isn’t actually producing any uranium right now, it earns some revenue from the mill ($963.000 in Q1, which then goes to the Anglo Pacific Group), some revenue from the management agreement with UPC ($817.000 in Q1), some revenue from the closed mines services ($2M in Q1) and some from the sale of mineral that was held in inventory ($852.000 in Q1).

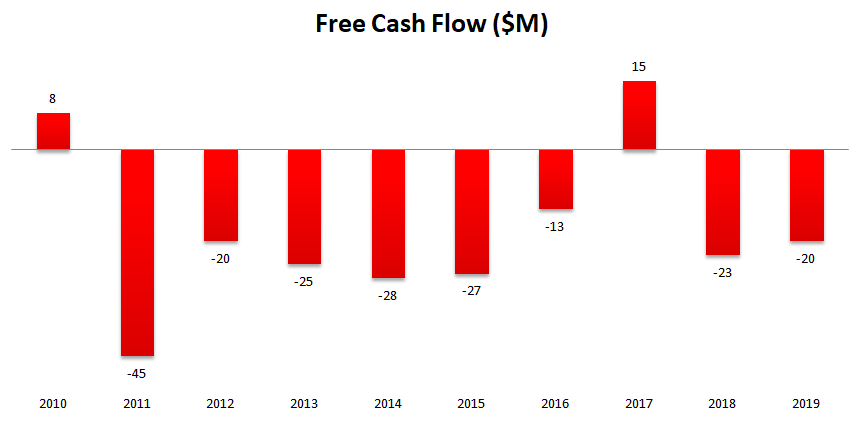

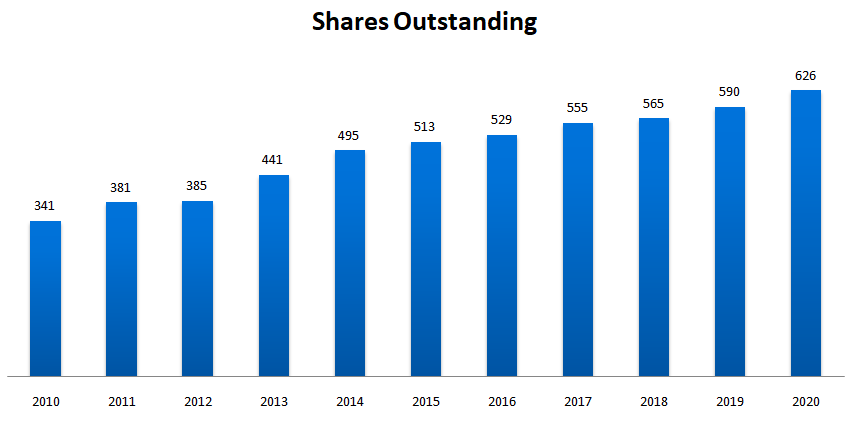

But this revenue hasn’t been enough to cover the costs and the company has lost money in 8 out of the past 10 years.

How has it survived? By frequently issuing shares. The most recent capital raise was in April when the company issued around 28 million shares for US$0,2 per common share for net proceeds of $6,8M. The company will use this money to fund ongoing activities in 2020.

I still can’t say if the proceeds of these equity raises have been well employed or not. I will leave that to the second round if I come back to Denison Mines.

Ok. Now let’s talk about liquidity. With the recent capital raise, the company should have Working Capital of $18M (adjusted) of which $12M would be cash. Before the lockdown, it was expecting a cash burn of -$15,5M for 2020. Remember that in the best-case scenario, they will only be in production in 2024 so they will have to raise cash many times before that. What we’ll need to understand is if the benefits of the future production will be higher than the dilution needed to get them.

RISKS

Permitting and dilution: These guys are planning on injecting an acidic solution into the ground. Although they have their redundant safety measures and this technology is not new in other parts of the globe, it would be the first time such a technology would be used in Canada so permitting is kind of an unknown and could take more time than expected (as all things uranium). I feel this is a very real risk.

DENISON MINES CONCLUSION:

At this stage, it’s clear to me that investing in Denison Mines is a bet on them getting the permit. To get the permit, they need the Environmental Assessment Process that is now on standby so the chances are we won’t be seeing any cash flows from this company for more than 5 years. They might sell some assets in the meantime.

But that doesn’t mean that its share price won’t go up if the uranium price rises. And this why they call this speculation rather then investment. We are not only speculating that the company will be able to get the permit and sell those pounds of uranium, but we are also speculating that the share price will go up much sooner than those cash flows become a reality.

These guys could also be a take out target, meaning that they could easily be bought. I’m not saying now, but in the future. Remember that Cigar Lake will be depleted before the end of the decade and Cameco must replace those pounds.

Conclusion

So here it is. We’ve looked at two different uranium companies and we’ve seen how different a producer is from a developer.

A quick comparison between the two tells me that if the turnaround in the uranium cycle takes longer than expected, Cameco will be a much safer bet than Denison, and although we’ve seen the spot price rally 35% this year to the current US$33,5, Cameco has said on its latest conference call that they’re still not seeing the utilities coming to the negotiation table in numbers that would mean a turnaround is here to stay. On the other hand, when that turn around finally happens, Denison’s share price will go up many times fold whereas Cameco will have a limited upside.

DISCLAIMER

The material contained on this web-page is intended for informational purposes only and is neither an offer nor a recommendation to buy or sell any security. We disclaim any liability for loss, damage, cost or other expense which you might incur as a result of any information provided on this website. Always consult with a registered investment advisor or licensed stockbroker before investing. Please read All in Stock full Disclaimer.