Why using the Price/Sales ratio

is wrong!

By Manuel Maurício

April, 2021

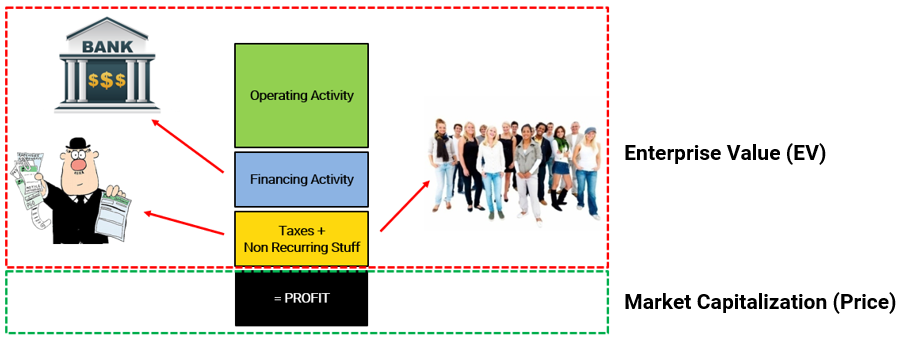

The way it usually goes when investors are valuing a company with the use of multiples is that they start with the Price/Earning ratio, and if the company isn’t profitable, they’ll go up the Income Statement to use the EV/EBIT or EV/EBITDA instead.

For those companies that are also not profitable on an EBIT basis, investors keep going up the Income Statement to the Sales or Revenue level. But when they get there they flip back to comparing it to the Price and not the Enterprise Value. Shouldn’t they be using the EV/Sales ratio instead of the Price/Sales?

In this article, I’ll be explaining why the Price/Sales ratio is technically wrong and why investors should use the EV/Sales instead.

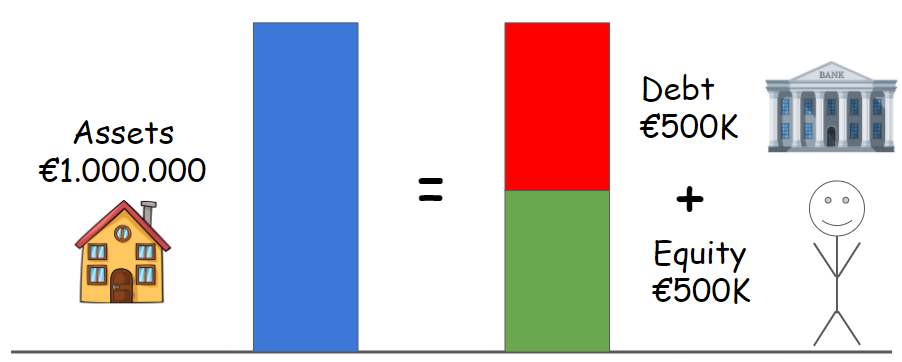

Let’s use a rental house as an example. Let’s say that we want to buy a house that costs €1 million euros. Half of that we’ll pay from our own pocket, the other half we’ll borrow from the bank.

I won’t go into detail on how to accurately calculate the Enterprise Value of a company on this article. For simplicity sake, let’s just say that the Enterprise Value is the total value of the company, regardless of whether it’s financed with equity or debt.

The simplified version of the formula is:

Enterprise Value = Market Cap (+) Debt (-) Cash.

In the example above, the Enterprise Value for the house is €1 million whereas the Market Cap is only half of that, €500 thousand.

Remember, the Market Cap isn’t the whole value of the house. It’s just the market value of the shareholder’s equity.

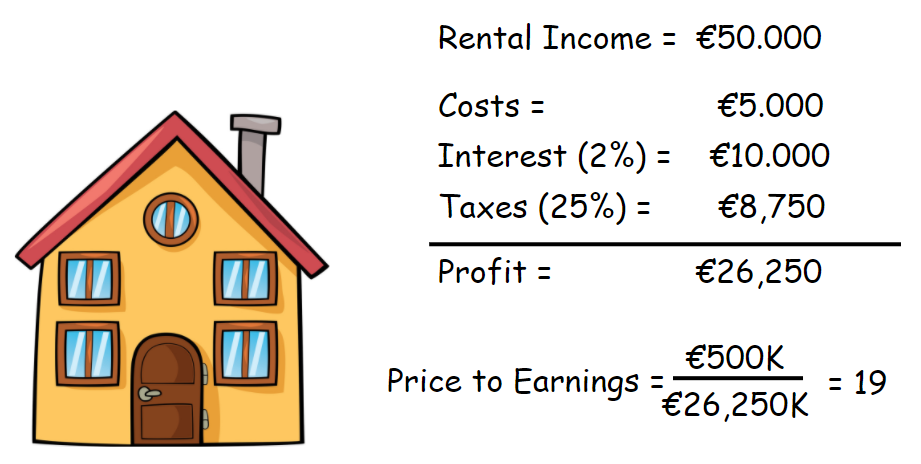

Let’s say that we’re planning on renting the house for €50 thousand per year. Let’s also say that the costs of owning the house are €5 thousand (stuff like bills, maintenance, legal costs, etc) and we’ll also pay interest in the amount of €10 thousand.

After deducting all of those costs and taxes, our profit will be €26.2 thousand, or a 5,3% return on our investment. Said in another way, we bought the house at a Price/Earnings of 19x.

As owners of the equity, those €26.25 thousand will go into our pocket.

That is why we compare the Earnings (or Net Income) with the Price (or Market Cap); because it’s the equity holder who has a claim on those profits.

Now let’s say that this house doesn’t have any earnings, but we still want to find a valuation multiple for it. What do we do? That’s right, we go up the Income Statement, typically to the next “earnings proxy”, the Operating Income, also called the EBIT (we can also use EBITDA or EBITA, but it’s irrelevant to the point).

But now we’re looking at an amount that doesn’t belong only to the owners of the equity (the shareholders), but to other stakeholders as well. Among those, we’ve got the creditors, the Tax authorities, the minority interests of non-controlling owners of subsidiaries, etc. All of those entities, together with the shareholders, have a claim on that money.

That’s why we compare the EBIT with the Enterprise Value, and not just the value of the equity. We must match the numerator with the denominator. That’s why the multiple is EV/EBIT, and not Price/EBIT.

Let’s suppose that the house we’re looking at is currently being poorly managed and it doesn’t generate profits even on an operating level. What can we do? We might want to forget about that house, but if we believe that somewhere in the future we can influence its operations to make it profitable, we might want to go even higher on the Income Statement to the Revenue level (or Sales).

Now the question arises, doesn’t the Revenue also belong to all of the stakeholders? Of course it does. That’s why we should compare it to the Enterprise Value.

Let’s take a look at another example.

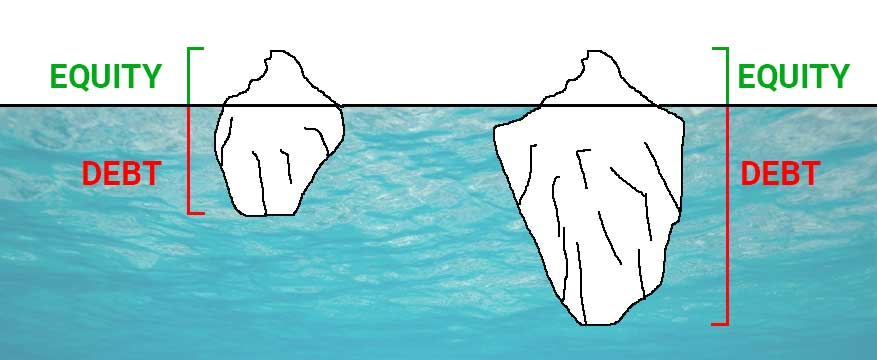

The tale of an iceberg!

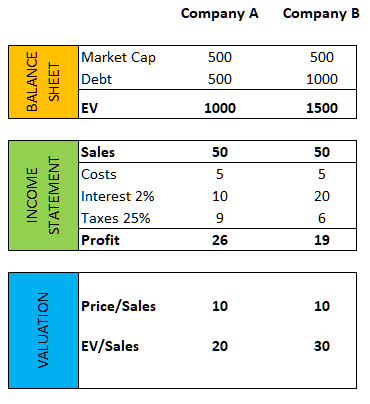

Let’s say that we’re looking at two different companies , Company A and Company B, both with a Market Cap of €500 million and sales of €50K.

With this information alone, we could be inclined to think that both companies were equally valued from a Price/Sales point of view. But that isn’t so. Because of debt.

Company A is conservatively financed with a Debt/Equity ratio of 1x, whereas Company B is a bit more aggressively financed at 2x.

If we factor in the value of the debt, we can see that Company B is more expensive than Company A. But if we were to calculate the Price/Sales ratio for each of the companies, we would have gotten 10x and we might’ve thought that they were equally valued.

CONCLUSION

Although you’ll see many competent investors using the Price/Sales ratio, and even if it might make some sense to use it when there’s no debt or excess cash involved, I hope this article has helped you to understand the principle behind the use of Enterprise Value.

When comparing companies within the same sector, and if you’re looking at the sales level, be sure to use the value of the whole enterprise and not just the equity value.

If you want to learn how I use concepts like this to pick the best stocks, consider joining the All in Stocks Subscription by clicking the button below:

Obrigado pelo teu interesse!

Enviámos-te um e-mail.

DISCLAIMER

The material contained on this web-page is intended for informational purposes only and is neither an offer nor a recommendation to buy or sell any security. We disclaim any liability for loss, damage, cost or other expense which you might incur as a result of any information provided on this website. Always consult with a registered investment advisor or licensed stockbroker before investing. Please read All in Stock full Disclaimer.